Redding novelist's crime caper -- Car thieves and drug runners

By DAN BARNETT

Steve Brewer and his family moved to Redding after spending 20 years in New Mexico, when "my wife's career took us to Northern California in 2003." According to interview materials supplied by his publisher, Brewer syndicates a regular humor column through The Albuquerque Tribune and has published a number of well-received mysteries, such as "Bullets," which, says Tony Hillerman, "gives crime fiction fans all the unforgettable characters and fast, fierce action we crave, plus a flavorful overlay of the wry Brewer humor we've come to love."

The author also writes the Bubba Mabry series and his new novel, "Bank Job," to be published in October by Intrigue Press, is set in Northern California.

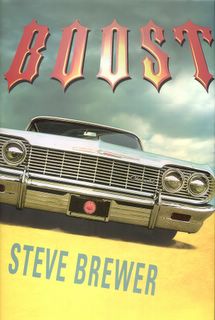

"Boost" ($24 in hardcover from Speck Press) is the 11th novel Brewer has published, and it's less a mystery than a rollicking and rambunctious adventure tale of almost-heart-of-gold car thieves pitted against Phil Ortiz, a dastardly businessman whose insatiable greed for acquiring and showing off classic cars has driven him to a lucrative drug-running sideshow. All the main characters are pretty much adrenaline junkies.

The word "boost," of course, is a slang expression for stealing a car, and that's exactly what 37-year-old Sam Hill does. He's in cahoots with the lovely Robin Mitchell, who continues to run Mitch's Auto Salvage the way her late father did. Old Mitch would hire Sam to deliver just the right car to special clients -- though Robin, with a computer science degree from the University of New Mexico, was making more money selling legitimately-obtained car parts over the Internet.

This is how it used to be: "Some customer would tell Mitch he wanted a '71 Mustang fastback like the one he drove in high school. Sam would steal such a car and deliver it to Mitch, who'd lovingly restore and repaint it, give it a new identity, and sell it to the nostalgic client for thirty grand. Sam and Mitch make money, the client gets his car, insurance pays off the stiff who lost the Mustang. And if the poor victim wants a car like the one he lost, well, he should come see Mitch."

But this is now. "Boost" is a story of a boost gone awry, about "a hot 1965 Thunderbird with a gold metal-flake paint job" with a stiff in the trunk. And no ordinary stiff -- the man was a drug informant. Someone had specifically asked for Sam to appropriate the car, and tipped off the police, and Sam is hopping mad. He is a car thief, after all, and not a murderer. Who would have it out for Sam Hill?

Our hero is determined to find out. What follows is a page-turning exposition of scheme and counter-scheme (Sam gets the stuffing beaten out of him on more than one occasion) as he tracks down the perp. But Sam has more than revenge on his mind. When Robin visits him in the hospital as he is recuperating from one of his encounters, she brings Sam flowers in a "howling coyote vase. The Trickster," Sam thinks. "She had him pegged. All his life, Sam had a fetish for practical jokes. To see others flustered and confused by some trick he'd arranged was the sweetest little thrill." Ortiz had met his match. Or had he?

When one is facing some pretty bad dudes, one needs some muscle of one's own. That's where Waymon Wayne Henderson comes in. A nightclub bouncer, Way-Way was "six-foot-seven, 290 pounds, maybe 5 percent body fat" -- a rather impressive character. Way-Way, Sam, Robin, and Billy Suggs -- an orphan Sam had befriended and saved from a life of crime by teaching him the boosting business -- pit brains and brawn and sarcasm against the real bad guys.

This is the kind of story that has you rootin' for the car thieves (who, of course, will all go straight after just one more trick). Brewer's dialogue is snappy and his descriptions wonderful. Lorena Alvarado, Sam's hard-bitten bulldog of an attorney, "dug around in her leather handbag, came up with a thin brown cigarette. She clamped it between her teeth and torched the end of it with a Bic lighter, then pulled her overcoat tighter around her bulging body. A sharp wind riffled her short black hair . . . smoke trailing out her snout."

"Boost" is a sweet little thrill.

Dan Barnett teaches philosophy at Butte College. To submit review copies of published books, please send e-mail to dbarnett@maxinet.com. Copyright 2005 Chico Enterprise-Record. Used by permission.