Award-winning science-fiction author to speak in Chico on global warming

By DAN BARNETT

Kim Stanley Robinson has written a series of novels of the near future, meshing hard science with ecological speculation, and has won a shelf full of Hugo and Nebula awards for his efforts.

His Mars trilogy is a multi-generational saga of the colonizing -- and terraforming -- of the red planet; "Antarctica" is an exploration of the political and environmental future of the South Pole.

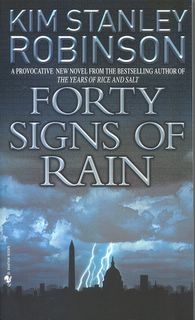

Now, with "Forty Signs of Rain" ($7.99 in paperback from Bantam), Robinson begins a new trilogy in which political inaction and scientific cowardice reap the whirlwind. Washington, D.C., is flooded and then (in the second volume, "Fifty Degrees Below," to be published next month) frozen. With descriptions eerily reminiscent of the inundation of New Orleans and other Gulf Coast communities, "Forty Signs of Rain" reads more like recent history than science fiction.

Robinson will discuss his work, and his views on global warming, in a free presentation at Chico State University's Laxson Auditorium at 7:30 p.m. Friday. Sponsored by Chico State Office of the Provost, Robinson's lecture is open to the public but a ticket is required from the University Box Office, located on the corner of Second and Normal streets.

The driving force of "Forty Signs" is the claim that there is an ecological "tipping point" in which cumulative changes in the oceans and the atmosphere can alter the earth's climate -- in as little as three years.

Robinson's novel is purposely prosaic, with long stretches recounting the happy home life of National Science Foundation statistician Anna Quibler (an appropriate name for someone in her line of work) and her husband Charlie, an environmental advisor to Democratic Senator Phil Chase. Charlie is a telecommuter who cares for young sons Nick and Joe while Anna works at NSF headquarters in Arlington, Va., vetting grant applications from researchers.

Her co-worker, Frank Vanderwal, single, on loan from UC San Diego, had helped found a biotech startup in that city. Frank's interest in Torrey Pines Generique was now in a blind trust, but there are hints that a hotshot biomathematician employed by Torrey Pines has developed a statistical way to increase the likelihood that bioengineered proteins might be more readily accepted by the body. Frank realizes that a patent on such a method might mean a windfall for the company, and part of the novel deals with Frank's efforts to deny NSF funding for the mathematician's proposal (which would have meant public access to his findings).

For the longest time I couldn't figure out how the medical research conducted by Torrey Pines connected with global warming, but there are hints in the book (maybe this is a spoiler) that the technique might be applied to plant materials to enable them to better absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, thus lessening the impact of greenhouse gasses.

All of this is more than theoretical. The story focuses on the political fortunes of a group of pizza-loving Buddhists representing the small island nation Khembalung, which is flooded more and more often. Befriended by Anna and Charlie, they attempt to persuade Senator Chase to push harder on environmental legislation.

Frank, the cynical worshiper of reason, is changed by the Buddhist emphasis on compassion (as well as by an encounter with a mysterious and desirable woman in a stuck elevator). "The truth is," he tells his colleagues near the end of the first volume, "we have enough data already. The world's climate has already changed. The Arctic Ocean ice pack breakup has flooded the surface of the North Atlantic with fresh water, and the most recent data indicate that that has stopped the surface water from sinking, and stalled the circulation of the big Atlantic current. ... Scientists should take a stand and become part of the political decision-making process."

That may not happen; the Republican president's science adviser is, thinks Charlie, "a pompous ex-academic of the worst kind, hauled out of the depths of a second-rate conservative think tank when the administration's first science advisor had been sent packing for saying that global warming might be real and not only that, amenable to human mitigations. ... Easier to destroy the world than to change capitalism even one little bit."

Then it rains, with flooding, rescue boats, hints of looters. D.C. survives. But, says Robinson, the tide has most definitely turned.

Dan Barnett teaches philosophy at Butte College. To submit review copies of published books, please send e-mail to dbarnett@maxinet.com. Copyright 2005 Chico Enterprise-Record. Used by permission.

No comments:

Post a Comment