The Karakoram Highway (KKH) in Northern Pakistan "is one of the most daunting engineering projects humans have ever attempted. Hewing principally to the rugged Indus River Gorge, the KKH has cost the life of one road worker for each if its four hundred kilometers."

Named after the nearby Karakoram Range (giving the letter designation to one of its mountains, K2, the second highest peak in the world), the highway project forms a starting contrast to a very small, very quiet, but in some ways equally daunting project undertaken by mountaineer Greg Mortenson: The construction of a school, for boys and especially for girls, in a little village in the Baltistan area of Northern Pakistan.

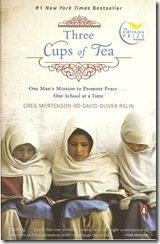

The true story is told in "Three Cups of Tea: One Man's Mission to Promote Peace . . . One School At a Time" ($15 in paperback from Penguin) by Mortenson and David Oliver Relin. Mortenson's co-author spent two years interviewing many who touched his life; he found a life that touched many others in its single-minded determination to make a quality education (and actual school rooms) available to village children living at the edge of existence.

In advance of Mortenson's April appearance in Chico, Chico State University (www.csuchico.edu/bic) and Butte College (www.butte.edu/bic) have designated "Three Cups of Tea" as the "Book in Common"; other community organizations are also starting discussion groups and the E-R will be archiving stories dedicated to Mortenson's work.

Tragedy and failure have haunted Mortenson's life. After his sister Christa died of a seizure on her twenty-third birthday Mortenson in 1993 wanted to place her necklace at the summit of K2, but he failed to reach the top. He got turned around in his descent and entered an unfamiliar village, Korphe, where he met Haji Ali, the village chief, who told him sharing the third cup of tea means "you join our family."

Mortenson promised to return and build a school, and the story (told in the third person) traces the circuitous route he took to keep that promise. Hounded by failure, then by success, Mortenson is complex: An infidel in a Muslim land who gained respect and love from religious authorities, whose vision of building schools continues today, and whose inner climb is the most inspiring of all.