The 1968 siege of Khe Sanh -- A Chico visitor's Vietnam memoir

By DAN BARNETT

Michael Archer, who lives in Reno with his wife and three children, signed up for the Marines in 1967.

He and his best friend, Tom Mahoney, enlisted not for patriotic reasons but, for Tom, to get out of Oakland, and, for Michael, to live the adventure and "to prove myself." By 1970, with the Corps downsizing, Michael was released to civilian duty after a tour of Vietnam and months spent in Khe Sanh during its siege by soldiers from North Vietnam. Tom would never return.

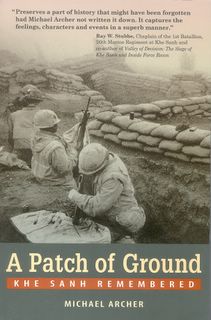

Archer had long wanted to write his story, but earlier attempts brought too much emotion. Now, drawing on his own records and the published accounts of others, "A Patch of Ground: Khe Sanh Remembered" ($15.95 in paperback from Hellgate Press) takes the reader into the heart of the U.S. war in Vietnam told in very human terms. Archer's prose is vivid and detailed, the account of his actions "in country" both humble and humbling, and the incidents he relates sometimes darkly humorous and sometimes intensely frightening. There are more than two dozen black-and-white photographs with several maps to help orient the reader.

A radio operator out of the Khe Sanh Combat Base, located not far from Laos and the Demilitarized Zone that separated North and South Vietnam, the author is surrounded by unforgettable characters: Tiddy, Pig, Old Woman (known for his constant high-pitched complaining), Savage, Captain Mirzah "Harry" Baig and many more. Archer's deft style draws the reader into the story so that it becomes more than ancient history.

Michael Archer will be coming to Chico for public appearances and a luncheon for Khe Sanh veterans. He will be signing books at 6 p.m. Friday at Lyon Books in Chico and at 3 p.m. Saturday at Barnes & Noble. In a letter Archer writes, "January 21st has special significance to the survivors of the 1968 siege of Khe Sanh because it is the anniversary of the day that momentous battle, the most protracted, costly and consequential of the Vietnam War, commenced."

The statistics, as recounted in "A Patch of Ground," are hard to grasp. "Over 1,000 Americans died fighting for Khe Sanh in 1968, and another 4,500 were wounded. ... South Vietnamese military losses were in the range of 750 dead and 500 wounded. The North Vietnamese Army suffered nearly 12,000 dead with probably twice that many wounded."

The book's central chapter, "Overrun," is the most harrowing. Archer is on radio duty at Khe Sanh Village. Early the morning of Jan. 21, 1968, word comes from the combat base "putting all forces in the area on red alert." Minutes later, "gunfire ... encircled the compound and, mixed with our outgoing fire, created an unbelievable racket. The deafening roar in the center of a pitched battle nearly defies description: a seamless earsplitting blend of chattering bursts of semi-automatic rifles, the oscillating knock of machine guns, teeth-jarring detonations of rocket-propelled grenades, and the deep, reverberating thump of exploding mortar shells. ... Alone in the bunker, fear cramped my neck muscles and tremors shook my head like a seizure. Tears filled my eyes and I started to repeat the same question aloud, 'What am I gonna do? What am I gonna do?'" The reader cannot turn away.

When Archer returned home to the Oakland-Berkeley area at the height of anti-war sentiment, his "anger and frustration were sometimes overwhelming." No one seemed to understand "the unconscionable brutality of North Vietnam's terror apparatus." Willard Park in Berkeley became "Ho Chi Minh Park" and mailboxes were painted to resemble Viet Cong flags. Archer blamed the hippies for their romanticism, the politicians for wavering, the military for dishonest assessments and admits to decades-long bitterness which "eventually, mercifully, sputtered out." Then he could write.

The war, he realized, was a kind of noble futility. He would think of the tens of thousands who lost their lives and remember "the insolent young faces of my buddies, the fine red dust of Khe Sanh etched into their every pore (and) the ease, humor and courage with which they endured such relentless peril."

"In those moments," he writes, "it did not matter how I felt about the war, the nation that wished to forget, or myself. It mattered only that I was proud to have stood with them and defended a little patch of ground."

Dan Barnett teaches philosophy at Butte College. To submit review copies of published books, please send e-mail to dbarnett@maxinet.com. Copyright 2006 Chico Enterprise-Record. used by permission.

No comments:

Post a Comment